When the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) publicizes financial penalties it has levied against employers for overtime pay violations, it’s not hoping to shame them. The treatment and calculation of this pay can be confusing. So the DOL’s goal is to make the most of “teachable moments.” Three recent cases involving OT pay rules come under that heading.

Before diving into the details of those cases, here’s a review of the rules as laid out in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), for administering OT, plus one alternative way to calculate OT in some situations:

- OT pay, equal to 150% of the employee’s basic wage, must be paid on the employee’s regular payday, for all hours worked over 40 hours during a workweek.

- A “workweek” is defined by the DOL as “a fixed and regularly recurring period of 168 hours,” that is, seven consecutive 24-hour periods. This definition prevents employers from using longer periods of time to determine average hours worked when calculating overtime pay eligibility.

- Employers can set the beginning and ending of the 168-hour period as they see fit.

- The FLSA doesn’t require a higher hourly pay rate during weekends or holidays. However, employers that do pay premium rates at times must incorporate the higher rates into the OT pay calculation.

- In addition to the basic hourly wage rate, employers must add in other “remuneration for employment” including discretionary bonuses, gifts and pay for times when an employee isn’t actually working because of a vacation, holiday or being out on paid sick leave.

- Nonexempt salaried employees (except as noted below) earn OT pay based on 150% of the hourly equivalent of their salary, that is, the salary divided by 40 hours. (Even if an employee’s normal workweek consists of fewer than 40 hours, to be eligible for OT pay, the employee still needs to exceed 40 hours).

The Fluctuating Workweek OT Calculation

The OT pay calculation formula for nonexempt salaried employees whose hours regularly vary from week to week can be a little different. This is possible when it’s made clear to the employee that weekly pay won’t be reduced below the base amount even when fewer than 40 hours are actually worked. But under this optional fluctuating workweek method, these employees are still entitled to OT pay when they work more than 40 hours.

Here’s how it works:

Say, for example, an employee’s weekly salary is $600, and he or she works 50 hours in a week. The hourly rate for overtime wage calculation purposes would be based on $600 divided by the total hours worked during that workweek, that is, $600/50 = $12 an hour. The overtime earned would be half of the hourly rate (that is $6) for the 10 hours exceeding 40. So, $60 would be the amount of overtime pay added to the $600 base salary that week.

Recent DOL Cases that Illustrate OT Violations

Case One: Where the Buck Stops

The first case involves use of a staff leasing company for temporary workers. Some employers learned the hard way that using a leasing company didn’t mean they were off the hook for OT pay. In fact, paying workers what they are owed is a joint responsibility shared by the leasing company and their employer client.

“Leased or temporary employees are entitled to the same workplace rights as other employees,” according to the DOL. This case involved three restaurants in Key West that all used the same staffing company. The back-pay settlement totaled $162,310 and involved 45 workers.

Case Two: Multiple Issues

In the second case, 30 employees of a Florida roofing company recovered an average of $10,000 in unpaid overtime pay. How did the calculation error occur? The employer didn’t include production-related and profit-sharing bonuses earned by the employees when determining their hourly OT pay rate.

In the same case, the DOL found that the employer failed to log the start and stop times of employees who were paid on a piece-rate basis. Doing so is a fundamental recordkeeping requirement.

Yet another mistake was made by the roofing company when it allowed employees to “bank” OT. The employer “allowed workers to draw from the overtime bank as needed in the form of gift cards or other advances.” That regime didn’t comply with the FLSA’s requirement that OT dollars be paid to employees on their payday for the already defined workweek.

Case Three: Misclassification

The third recent DOL overtime pay case involved 43 workers and a security services company. The workers weren’t paid OT because they were wrongly classified as independent contractors. Such misclassification is common in the security and construction industries, according to the DOL.

The answer to whether a worker is an employee under the FLSA or an independent contractor “is a legal question determined by the actual employment relationship, not simply by title, choice, or industry practice,” the DOL stated. But it’s true that the FLSA and its overtime pay requirements doesn’t cover workers who can pass muster as true independent contractors.

Parting Words

It’s common for employers to treat OT pay as an arrangement between themselves and their employees, and they may not even be aware that the arrangement violates the established rules. An example is the company that kept an OT bank. But in the world of work, rules that are bent or broken will eventually be held up to the light of day to see how they compare to employment law. Before that happens, consider reviewing your current OT pay practices to ensure that you’re in sync with the FLSA.

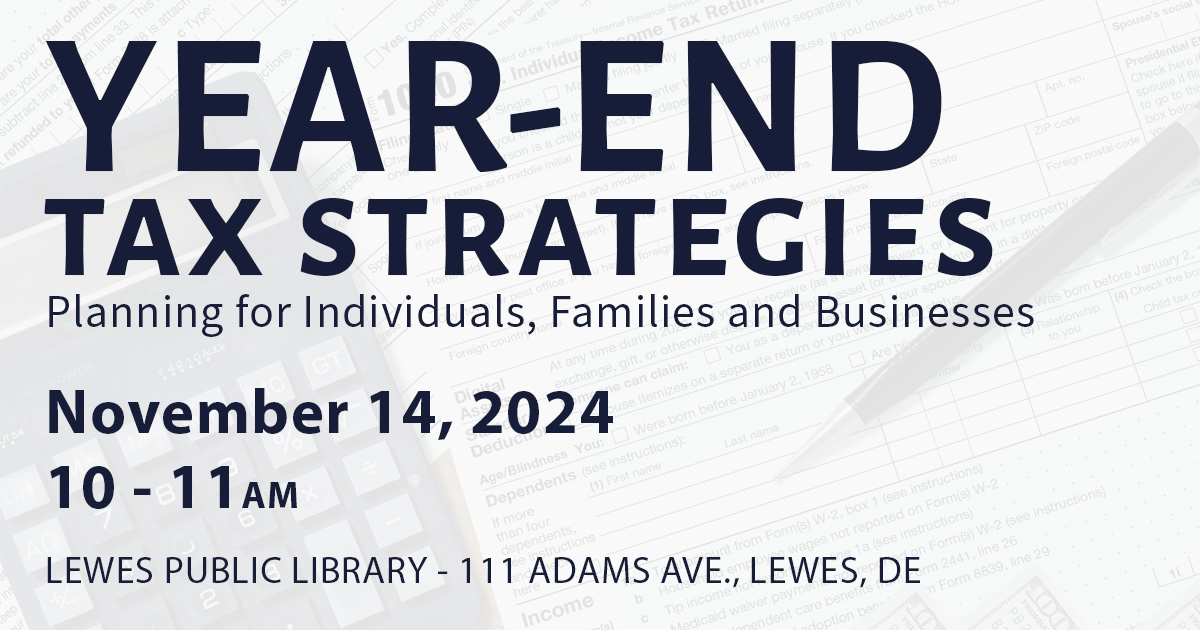

PKS & Company, P. A. is a full service accounting firm with offices in Salisbury, Ocean City and Lewes that provides traditional accounting services as well as specialized services in the areas of retirement plan audits and administration, medical practice consulting, estate and trust services, fraud and forensic services and payroll services and offers financial planning and investments through PKS Investment Advisors, LLC.

© Copyright 2021. All rights reserved.

Brought to you by: PKS & Company, P.A.